Summary

This analysis tests public attitudes on the importance of, benefits of and criteria for citizenship. The findings provide policy ideas for — and a strong case to — this Conservative Government for reforming the citizenship process.

The key findings are:

- A clear majority of the British public think it is important for immigrants living permanently in the UK to become citizens (60%).

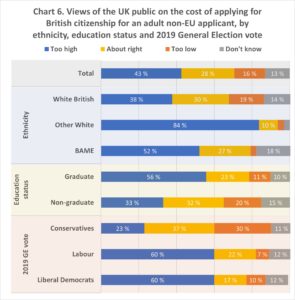

- The UK public are more likely than not to believe that the current cost to an applicant of applying for citizenship as an adult non-EU applicant is too high (43%) rather than about right (28%) or too low (16%).

- The UK public thinks it should be cheaper for certain immigrant groups to become citizens, especially immigrants who work in key frontline sectors such as social care or the NHS (78%), immigrants with skills which are in shortage (75%) and immigrants who have worked and paid taxes in Britain for more than five years (75%).

- The UK public thinks it should be quicker for immigrants who work for the NHS (57%), immigrants who are key workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (55%) and immigrants who work in social care (50%) to become citizens.

- A majority of the public support discounted citizenship fees for children born and raised in the UK by parents who are not British citizens (72%).

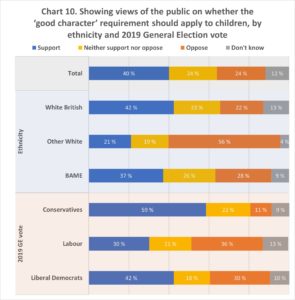

- The UK public are more likely than not to believe that the Home Office should continue to apply the ‘good character’ requirement to child citizenship applicants (40% versus 24%).

- A clear majority of the UK public support the introduction of birthright citizenship (53%).

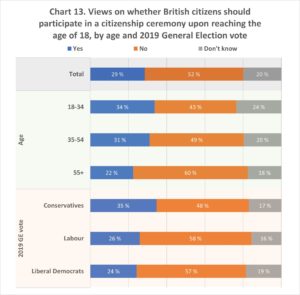

- A plurality of the UK public believe that citizenship ceremonies have a role to play in the social integration of immigrants (42%), but reject the idea that they should be extended beyond new citizens to all British citizens (52%).

Being a Conservative or a Leave voter is usually associated with less positive views about citizenship, while being a Labour, Liberal Democrat or Remain voter is usually associated with more positive views. Meanwhile, belonging to an older age group or being a non-graduate is sometimes associated with less positive views about citizenship, while being younger or being a graduate is sometimes associated with more positive views.

Based on our findings, Bright Blue proposes three new policies that the Government should introduce:

- The Government should shorten the settlement requirements for all non-citizen COVID-19 key workers to two rather than five years, significantly reduce their residency fee by at least 75% and waive their citizenship application fee.

- The Government should introduce discounted citizenship fees of at least 50% for all low-income migrants.

- The Government should introduce free citizenship for children born and raised in the UK by parents who are not British citizens.

Introduction

Domestic and international research demonstrates that gaining citizenship is beneficial to immigrants, both materially and psychologically. Becoming a citizen is associated with increased civic engagement,[i] a greater sense of belonging[ii] and — particularly for the most disadvantaged immigrants — enhanced employment opportunities.[iii]

Considering the individual and societal benefits of citizenship, it is concerning that there was an overall decline in citizenship applications over the last decade, from 197,000 in 2010 to 148,000 in 2020.[iv] This occurred even as the proportion of the population who are immigrants continued to rise and, as a result of Brexit, an increase in EU citizens applying for UK citizenship.[v]

Successive Governments in recent decades have deliberately tried to make applying for citizenship harder. Since 2006, permanent residency and citizenship fees have consistently and markedly increased beyond the administration costs of the applications themselves in a bid to profiteer and compensate in part for the effects of Home Office spending cuts.[vi] Britain now has some of the highest citizenship fees in the world,[vii] with the application costing £1,330 per adult. Indeed, for non-EU immigrants — who also pay a hefty fee of £2,389 to apply for Indefinite Leave to Remain prior to making a citizenship application — the cost of the citizenship application process from start to finish is £3,719.[viii] This is despite the fact that the cost to the Home Office of processing a permanent residency application is only estimated to £243 and for a citizenship application is estimated to be only £372, meaning that for each adult citizenship application the Home Office sees considerable profits. The total profit for the Home Office was estimated to be £203 million for permanent residency applications and £96.6 million for citizenship applications in 2018.[ix]

In light of the evidence on the benefits of citizenship and the worrying decline in citizenship applications in the last decade, we wanted to test public attitudes on the importance of, benefits of and criteria for citizenship. This analysis might provide policy ideas for — and a strong case to — government for reforming the citizenship process.

There has been some polling on public attitudes on citizenship, but it appears to overlook three particular aspects. First, testing attitudes towards specific and detailed elements of current citizenship policy. Second, examining what public appetite there is for reform of current citizenship policies. Third, testing how attitudes vary among different groups of people. Considering we have a Conservative Government, there is significant political value in understanding how Conservative voters think about citizenship, as this might make the Government more likely to reform certain current policies.

Methodology

Polling was undertaken by Opinium and conducted between 9th and 15th June 2020. It consisted of two samples; one nationally representative sample of 2,001 UK adults and a booster sample of 1,000 Conservative voters. The sample was weighted in terms of gender, age, region, education status, car ownership and occupation to reflect a nationally representative audience. We only highlight in our analysis significant difference in attitudes between different socio-demographic and political groups.[x]

The importance of citizenship

We first asked how important it is for immigrants who are permanently living in the UK to become citizens. This question aims to uncover just how important the UK public think citizenship is in the immigration process.

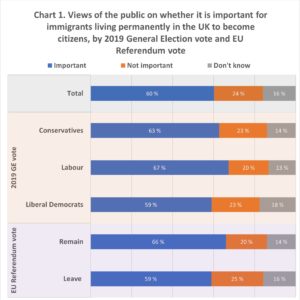

As Chart 1 below illustrates, a strong majority (60%) of the public believe it is important for immigrants permanently living in the UK to become citizens. However, a significant minority of respondents (24%) deem it unimportant for immigrants permanently living in the UK to become citizens.

Base: 2,001 UK adults

On the question of whether or not it is important for immigrants living permanently in the UK to become citizens, there is only negligible variation across socio-demographic groups.

As Chart 1 above illustrates, there is strong cross-party consensus in favour of long-term immigrants becoming citizens. There is only minor variation between party groups, with Labour voters being the most likely to say that it is important for immigrants living in the UK to become citizens (67%), followed closely by Conservative (63%) and Liberal Democrat voters (59%).

Interestingly, among Conservative voters, there is a pronounced difference in views by education status. Seventy percent of Conservative graduates say it is important for immigrants living in the UK permanently becoming citizens. In comparison, 59% of Conservative non-graduates do so. Contrastingly, the difference in support between graduates and non-graduates among the general public are small (62% versus 59%).

A majority of both Remain (66%) and Leave voters (59%) say that it is important for immigrants living in the UK to become citizens.

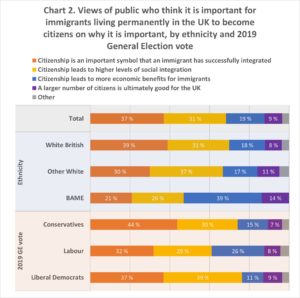

We went on to ask the majority of respondents who say it is important that immigrants living permanently in the UK become citizens to select one reason why they think this is the case. As Chart 2 below illustrates, ‘Citizenship is an important symbol that an immigrant has successfully integrated’ is the most common reason selected (37%), followed by ‘Citizenship leads to higher levels of social integration’ (31%) and then ‘Citizenship leads to more economic benefits for immigrants’ (19%).

Base: 1,206 UK adults

Ethnicity emerges here as a powerful differentiator of attitudes. This is unsurprising in the context that BAME and Other White respondents may be more likely to have interacted with the immigration and citizenship application system personally or through relatives.

Only 18% of White British respondents say it is important for immigrants living permanently in the UK to seek citizenship because holding ‘Citizenship leads to more economic benefits for immigrants’, in contrast to a plurality of BAME respondents (39%). Indeed, there is no other group, socio-demographic or political, more likely to identify this reason than BAME respondents.

There is some variation in attitudes by voting history. A plurality of Conservative (44%) and Labour voters (32%) and a significant minority of Liberal Democrat voters (37%) say it is important for immigrants living permanently in the UK to become citizens because ‘Citizenship is an important symbol that an immigrant has successfully integrated’. Liberal Democrat voters are the only group in which a plurality say it is important for immigrants living permanently in the UK to become citizens because ‘Citizenship leads to higher levels of social integration’ (39%). Labour voters were more likely (26%) than Conservative (15%) or Liberal Democrat voters (11%) to say that it is important for immigrants living permanently in the UK to become citizens because ‘Citizenship leads to more economic benefits for immigrants’.

Leave voters are significantly more likely than Remain voters to say citizenship is important because of its role as an important symbol of successful integration (50% versus 31%), but are less likely to say that citizenship itself leads to higher levels of social integration (27% versus 33%).

For balance, we also asked the minority of the public who say that it is not important for immigrants living permanently in the UK to become citizens to select one reason why they think this is the case. As demonstrated in Chart 3 below, the most popular reason is ‘Citizenship is not necessary for an immigrant to socially and economically participate in the UK’, with plurality support of 44%. This is followed by ‘We do not need any more people living in the UK to become citizens’ (32%) and ‘Citizenship is an empty symbol’ (11%). The least popular reason is ‘Citizenship is too expensive for applicants’ (9%).

Base: 477 UK adults

The difference in opinion between graduates and non-graduates is the most notable. A majority of graduates (56%) state ‘Citizenship is not necessary for an immigrant to socially and economically participate in the UK’ in comparison to minority of non-graduates (36%), while non-graduates (45%) are significantly more likely than graduates to choose ‘We do not need any more people living in the UK to become citizens’ than graduates (16%).

There is significant variation by voting history. A majority of Conservatives say ‘We do not need any more people living in the UK to become citizens’ (50%). Only 18% of Labour voters and 20% of Liberal Democrat voters agree, with the majority of Labour and Liberal Democrat voters who think it is unimportant for a long-term immigrant to become a British citizen saying that is because ‘Citizenship is not necessary for an immigrant socially and economically participate in the UK’ (56% and 60% respectively).

Looking at differences within Conservative voters, Conservative graduates (41%) are less likely than Conservative non-graduates (59%) to say that ‘Citizenship is not necessary for an immigrant to socially and economically participate in the UK’, though a plurality still do so.

There is also significant difference in opinion between all Remain voters and all Leave voters on the reason why becoming a citizen is unimportant for long-term immigrants. Whilst 60% of Remain voters selected ‘Citizenship is not necessary for an immigrant to socially and economically participate in the UK’, only 31% of Leave voters did so. For Leave voters, the most commonly selected reason is ‘We do not need any more people living in the UK to become citizens’ (53%), which only a small minority of Remain voters selected (11%).

Citizenship and Britishness

With a majority of the UK public in agreement that it is important for immigrants living permanently in Britain to become citizens, we investigated the link between citizenship and British identity, asking whether being a citizen automatically makes an immigrant British. This question seeks to ascertain just how important the UK public thinks citizenship is to being British.

As Chart 4 below illustrates, a plurality of the public (41%) say that though holding citizenship does not automatically make an immigrant British, citizenship is a key part of being British. A minority (25%) of respondents say that holding citizenship automatically makes an immigrant British. Therefore, a majority of the UK public say that becoming a citizen makes an immigrant British to some extent (66%). In contrast, a significant minority say that citizenship is not important in making an immigrant British (20%).

Base: 2,001 UK adults

Education is the only notable socio-demographic differentiator, with graduates (35%) more likely than non-graduates (18%) to say that holding citizenship automatically makes an immigrant British. Overall, however, a majority of both graduates (70%) and non-graduates (63%) agree that holding citizenship makes an immigrant British to some extent.

Along party political lines, a majority of all voters agree that citizenship makes an immigrant British to some extent, as can be seen in Chart 4 above. A plurality of Conservatives (49%) say that citizenship is a key part of being British, in comparison with a minority of Conservatives who say that citizenship automatically makes an immigrant British (19%).

Remain voters (36%) are significantly more likely than Leave voters (15%) to say that holding citizenship automatically makes an immigrant British. However, both a majority of Remain (73%) and Leave (62%) voters agree that becoming a citizen makes an immigrant British to some extent.

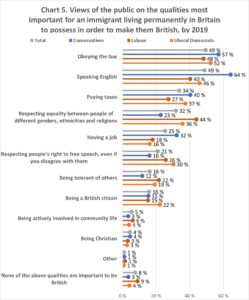

With a majority of the public believing that citizenship to some extent makes an immigrant British, we asked the public which three qualities are the most important for an immigrant living permanently in this country to possess in order to make them British. This question will help us determine the characteristics that the UK believes are most important for being British.

The three most common choices among the UK public — all with strong pluralities — are obeying the law (49%), speaking English (49%) and paying taxes (34%). These are shown in Chart 5 below.

Base: 2,001 UK adults

Only a small minority of respondents (16%) identify ‘being a citizen’ as one of the three most important qualities for an immigrant to possess in order to be British. This suggests that Britishness can be defined by citizenship to some extent, echoing the findings in Chart 4 earlier, but that other qualities are seen as more important by most of the public.

Age does not correspond with major differences in views on important qualities to be British, except for being able to speak English. While a clear majority (65%) aged over 55 selected ‘Speaking English’ as a most important quality, this fell to 29% of adults aged below 34.

There is also some variation in selection of the most important qualities by ethnicity. Notably, White British people are the most likely group (51%) to say that ‘Speaking English’ is a most important quality, well ahead of Other White people (40%) and BAME people (35%). Additionally, only 32% of Other White respondents say ‘Obeying the law’ is one of the most important qualities, in comparison with 52% of White British respondents and 51% of BAME respondents.

Furthermore, Other White respondents are significantly more likely than any other ethnic group to say ‘Respecting equality between people of different genders, ethnicities and religions’ is one of the most important qualities for an immigrant living permanently in Britain to possess in order to be British (47%), while only 31% of White British and 28% of BAME respondents made this choice.

Significant variations emerge by political groups, as shown in Chart 5 above. Most notably, 64% percent of Conservative voters say that ‘Speaking English’ is one of the most important qualities for an immigrant to possess in order to be British, which is notably higher than among Labour voters (40%). Conversely, 44% of Labour voters say that ‘Respecting equality between people of different genders, ethnicities and religions’ is one of the most important qualities, while Conservatives are considerably less likely to agree (23%).

Amongst Conservatives, there are interesting variations in attitudes by age. Seventy-five percent of Conservatives aged over 55 say that ‘Speaking English’ is one of the most important qualities for an immigrant to be British, in comparison with 59% of Conservative 35 to 54 year olds and 42% of Conservative 18 to 34 year olds. Differences in attitudes among Conservatives by age also emerge around ‘Obeying the law’. While only 38% of 18 to 34 year olds choose ‘Obeying the law’ as one of the most important qualities for an immigrant to be British, a majority of 35 to 54 year olds (56%) and those aged above 55 (64%) do so.

Among all voters, Leave voters are 29 percentage points more likely than Remain voters to say ‘Speaking English’ as one of the most important qualities for an immigrant living permanently in Britain to possess in order to be British (68% versus 39%). Conversely, Remain voters are 15 percentage points more likely than Leave voters to say that ‘Respecting equality between people of different genders, ethnicities and religions’ is a most important quality (39% versus 24%).

Citizenship fees

Britain has some of the world’s highest citizenship fees. Today, the cost for an adult British citizen application is £1,330, up from £268 less than two decades ago.[xi] Currently, the estimated cost to the Home Office of processing one of these applications is £372.[xii] Additionally, in order to apply for citizenship, applicants who are not EU citizens must first be granted Indefinite Leave to Remain and those who are EU citizens must be granted Settled Status. The application for Indefinite Leave to Remain also carries a cost of £2,389, despite the estimated cost of processing to the Home Office only being £243,[xiii] while there is no cost for receiving Settled Status. Inclusive of this cost, the total cost to an adult non-EU applicant making their way through the citizenship process is £3,719. For an adult EU citizen applicant, it is £1,330.

We asked the public their views on the cost of applying to be a British citizen for an adult non-EU applicant. As seen in Chart 6 below, a plurality of respondents say that the cost is too high (43%). In contrast, only 16% of respondents say that the costs are too low and 28% described them as about right. The UK public are much more likely to say the cost of citizenship is too high rather than too low.

Base: 2,001 UK adults

Differences emerge in public attitudes by ethnicity and education status, as Chart 6 above shows. While only 38% of White British people feel the total cost of applying for citizenship as an adult non-EU applicant is too high, a clear majority of Other White people (84%) and BAME people (52%) feel that it is.

There is strong divergence between graduates and non-graduates on whether the cost of citizenship application as an adult non-EU applicant process is too high. Graduates (56%) are considerably more likely than non-graduates (33%) to say the cost too high. Non-graduates are split between saying that the cost is too high (33%) or that it is about right (32%).

While clear majorities of Labour (60%) and Liberal Democrat voters (60%) say that the cost of applying for citizenship as an adult non-EU applicant is too high, only a minority of Conservative voters agree (23%). A plurality of Conservative voters say that the cost is about right (37%). In fact, a higher proportion of Conservative voters say the cost is too low (30%) rather than too high.

Among Conservatives, there is also a strong relationship between age and the likelihood of saying the total cost of applying for citizenship as a non-EU adult applicant is too high. Forty-three percent of Conservative 18 to 34 year olds say the cost too high, in comparison to 21% of those aged 35 to 54 and 22% of those aged above 55. A plurality of Conservatives aged 35 to 54 (32%) and above 55 (38%) say that the cost is about right.

The difference in attitudes between graduates and non-graduates is also evident but less pronounced among Conservative voters, with Conservative graduates (35%) significantly more likely than Conservative non-graduates (19%) to say the total cost of applying for citizenship is too high.

Across all respondents, Remain voters (59%) are significantly more likely than Leave voters (23%) to say that the total cost of applying for citizenship as an adult non-EU applicant is too high. Leave voters are split on the issue — 32% say that the cost is about right and 32% say the cost is too low.

In light of the public being more likely to say that the total cost of applying for citizenship is too high for an adult non-EU applicant, we asked whether particular immigrant groups should receive a discount on their citizenship fees. Currently, the UK does not provide discounted citizenship fees for any immigrant group, though citizenship application fees are less for children than they are for adults, as examined later in this analysis.

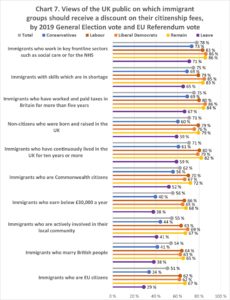

As Chart 7 below shows, the public are strikingly supportive of citizenship fee discounts, with majority support for all ten immigrant groups we proposed.

Base: 2,001 UK adults

Immigrants who work in key frontline sectors such as social care or the NHS are those most likely to be viewed by the UK public as being deserving of some form of discount (78%), closely followed by immigrants who have skills which are in shortage (75%) and immigrants who have worked and paid taxes in Britain for more than five years (75%).

That the public are especially receptive to discounts for immigrants working in key frontline sectors is unsurprising given the recent national focus on the pressures these workers have faced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, France is currently in the process of introducing fast-track citizenship for frontline COVID-19 workers including care workers and rubbish collectors.[xiv]

Meanwhile, the public believe that EU citizens are less deserving of discounted citizenship fees than all other immigrant groups, but a majority (51%) still say that they do deserve them.

Public attitudes to the deservingness of different immigrant groups vary by different social and political groups. In general, younger people are more willing to support discounted citizenship fees. For example, a strong majority of 70% of 18 to 34 year olds support a discount for immigrants earning less than £30,000 a year, roughly 20 percentage points more than any other age group. In the case of EU citizens, a majority (67%) of 18 to 34 year olds support a discount, again over 20 percentage points more supportive than the next most supportive age group of those aged 35 to 54 years (46%).

As shown in Chart 7 above, the majority of Conservatives support discounts for most of the immigrant groups we proposed. Conservatives are most likely to support citizenship fee discounts for immigrants who work in key frontline sectors such as social care or the NHS (73%). Immigrants who work in key frontline sectors are also the immigrant group who Labour and Liberal Democrat voters are most likely to support citizenship fee discounts for (83% and 86% respectively).

The only groups for which a majority Conservatives do not support citizenship fee discounts are immigrants who are actively involved in their local community (44%), marry British people (41%), earn below £30,000 a year (40%) and are EU citizens (34%). In contrast, a majority of Labour and Liberal Democrat voters support discounts for all four of these groups.

In general, there is little variation between Conservatives on which immigrant groups are deserving of citizenship application fee discounts, though there is some variation by age. For example, while a majority of 51% of Conservative 18 to 34 year olds support citizenship application fee discounts for EU citizens, only 35% of 35 to 54 year olds and 30% of those aged over 55 do.

Returning to all voters, a majority of Remain voters say all immigrant groups should receive a discount on citizenship fees. The difference in attitudes between Remain and Leave voters depends on the immigrant group. The most significant gap of 38 percentage points between Remain (67%) and Leave voters (29%) is over whether EU citizens should receive discounted citizenship fees.

It appears a majority of Leave voters may be more likely to support discounted citizenship fees where they perceive a clear benefit to the UK: for example, 67% of Leave voters support discounts for immigrants who have worked and paid taxes in Britain for more than five years and 65% support discounts for immigrants with skills that are in shortage.

The citizenship process

Fees are not the only barrier applicants face along their path to citizenship. In order to apply for British citizenship, applicants must have held Indefinite Leave to Remain or, in the case of EU citizens, Settled Status for at least a year and before that must have usually resided in the UK for five years.

Hence, we asked the public whether they think certain groups of immigrants should be eligible for a faster route to citizenship.

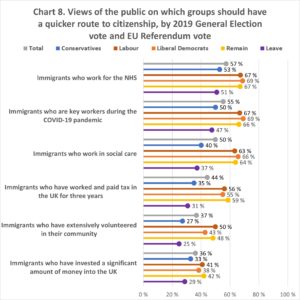

A majority of the public say that immigrants who work for the NHS (57%), immigrants who are key workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (55%) and immigrants who work in social care (50%) should receive a quicker route to citizenship, as shown in Chart 8 below. Again, support for these groups is unsurprising in the context of COVID-19.

Only a minority of the public support a quicker route to citizenship for immigrants who have extensively volunteered in their community (37%) and immigrants who have invested a significant amount of money into the UK (36%).

Base: 2,001 UK adults

While Labour and Liberal Democrat voters are in general very closely aligned on this question, Conservatives are significantly less in favour of giving particular groups of immigrants a quicker route to citizenship in comparison with all other voters. There is a slim Conservative majority in favour of an expedited citizenship route for only two group of immigrants: immigrants who work for the NHS (53%) and immigrants who are key workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (50%).

There is a significant gap between Remain and Leave voters in the case of all the immigrant groups suggested for a quicker route to citizenship, with Remain voters always being more supportive, unsurprisingly.

Children and citizenship

Children who are born in the UK do not automatically become British citizens if neither of their parents is already a British citizen. They must apply for British citizenship, irrespective of whether they were born in the UK and have grown up here. As of 2020, there are 412,000 children living in the UK who were born here but are not British citizens for this reason.[xv] In the wake of evidence that the parents of these children are put off from applying for citizenship for them because of the high cost — the fee for a child’s citizenship application is £1,021 — in December 2019 the High Court ruled that the child’s citizenship fee is unlawfully high and that the Government must review it.[xvi]

However, current Government policy is yet to change in response to this ruling and in October 2020 the complainants began the process of challenging child citizenship fees again, this time in the Court of Appeal.[xvii]

We tested public attitudes to the fee that non-citizen children born and raised in the UK must pay for their citizenship applications, as illustrated in Chart 9 below. We found that the UK public are more likely to support citizenship fee discounts for these children than many other immigrant groups in Chart 7.

A plurality of respondents (32%) say that these children should be able to apply for citizenship for free; 22% say these children should be automatically granted citizenship after living in Britain for five years; and 18% say these children should receive a discount on citizenship fees. Importantly, only 16% of the public say that these children should have to pay citizenship fees in full.

Therefore, a strong majority (72%) of the UK public are against the current citizenship fees for children of non-citizens born and raised in the UK.

Base: 2,001 UK adults

Other White (44%) and BAME respondents (39%) are more likely than White British (30%) respondents to say that the children of non-citizens born and raised in the UK should be able to apply for citizenship for free. White British (19%) people are much more likely to say that these children should pay their citizenship fees in full, compared to Other White (3%) and BAME people (6%).

Overall, a clear majority of Conservative voters are in favour of some form of dispensation for non-citizen children born and raised in the UK (59%), though not as supportive as Labour (85%) or Liberal Democrat voters (81%). Twenty-four percent of Conservative voters say that these children should be able to apply for citizenship for free and 22% say that they should be able to receive a discount on citizenship fees. However, a significant proportion of Conservatives (29%) say that these children should pay their citizenship fees in full, in comparison to small minorities among Labour (7%) and Liberal Democrat (9%) voters.

A plurality of 31% of Leave voters say that these children should pay citizenship fees in full. In comparison, only 7% of Remain voters agree. A majority of Remain voters (83%) say that these children should receive some special dispensation in terms of applying for citizenship — a plurality of Remain voters say that these children should automatically be granted British citizenship after living in the Britain for five years (35%), a significant minority of Remain voters say that these children should be able to apply for citizenship for free (34%) and a smaller minority say these children should simply receive a discount on their citizenship fees (14%).

In addition to fees, a barrier that non-citizen children born and brought up in the UK face on the path to citizenship is the ‘good character’ requirement. Though the ‘good character’ requirement — which must be met by both children and adults[xviii] applying for British citizenship — is not defined in law, factors that the Home Office consider include criminality and financial soundness. In 2019, the Joint Committee on Human Rights published a report calling for reform and criticising the government’s application of the test to children as young as ten.[xix]

We tested the UK public’s view on the application of the ‘good character’ requirement to children, informing them that it applies to all citizenship applicants over the age of ten[xx] and that some people who were born and raised in Britain are unable to get British citizenship because they fail the requirement, including for reasons that do not involve criminal behaviour.[xxi]

There is no great public appetite for change in the Home Office’s application of the ‘good character’ requirement to children — a plurality of respondents (40%) support it. However, there is some dissent, with a sizeable minority of 24% of the public opposing the application of this test to children. This is shown in Chart 10 below.

Base: 2,001 UK adults

As shown by Chart 10 above, the only socio-demographic group to see a majority (56%) oppose the application of the ‘good character’ requirement to child citizenship applications are Other White respondents. All other ethnic groups are more likely to be supportive of the application of the good character requirement to child citizenship applicants: White British (42%) and BAME (37%).

Politically, a majority of Conservative voters (59%) and a plurality of Liberal Democrat voters (42%) support the application of the ‘good character’ requirement to children. In contrast, a plurality of Labour voters oppose the application of the test to children (36%), though a significant minority of Labour voters do still support it (30%).

Among all voters, Leave voters (55%) are more likely than Remain voters (35%) to support the application of the ‘good character’ requirement to child citizenship applicants. However, Remain voters are split on the issue, with 35% supporting its application and 31% opposing it.

Reforming citizenship

There are innovative ways of reforming citizenship beyond fee discounts and fast-track routes. We asked the UK public to consider their support for the introduction of three different citizenship policies. First, economic citizenship, where citizenship is granted for a specified financial donation to the government or an investment, as is the case in Turkey.[xxii] Second, automatic citizenship by marriage, which would see anyone marrying a British citizen automatically becoming a British citizen as well. Finally, birthright citizenship, which would mean anyone born in the UK is automatically a citizen, as is the case in the USA.[xxiii] Currently, children born in the UK whose parents are both not citizens must apply for British citizenship and have no automatic right to it.

The UK public’s views of these different reforms are indicated in Chart 11 below.

Base: 2,001 UK adults

The concept of economic citizenship is unpopular, with 41% of the public opposed to its introduction versus 24% in support. The public are split over the idea of automatic citizenship by marriage (35% versus 35%).

However, support for the introduction of birthright citizenship finds majority support of 53%. Indeed, support for this policy proposal is steady across all socio-demographic characteristics, including age, ethnicity and education status, with support never dipping below 43%.

The introduction of birthright citizenship finds only plurality support among Conservatives (47%), in comparison with a majority of Labour (64%) and Liberal Democrat voters (60%). Support for birthright citizenship is much higher among Remainers (66%) than Leavers (47%).

Citizenship ceremonies

Finally, at the end of the application process for citizenship, new citizens have to partake in citizenship ceremonies. Introduced in 2004, citizenship ceremonies are now compulsory for all successful citizenship applicants. Applicants must each pay £80 to take part in the ceremony. During the ceremony, the applicant makes an oath of allegiance and pledges to respect the rights, freedoms and laws of the UK.

We sought public attitudes on this final stage of the citizenship process for a successful applicant.

We provided our respondents with statements according to a range of attitudes relating to citizenship ceremonies and asked them to state the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each one, as shown in Chart 12 below.

Base: 2,001 UK adults

The statement ‘Citizenship ceremonies are an important way to welcome new citizens’ attracts the most support among the UK public (46%). There is also evidence that significant proportions of the public see citizenship ceremonies as having value for social integration, with a plurality supporting the statement ‘Citizenship ceremonies help citizens build a sense of loyalty to Britain’ (44%) and the statement ‘Citizenship ceremonies help new citizens to feel British’ (42%).

However, we did find some public scepticism towards citizenship ceremonies. The statement ‘Citizenship ceremonies are a waste of money’ finds plurality support (42%) and so does the statement ‘Citizenship ceremonies have no special role’ (41%).

Additionally, all five statements saw over a third of respondents select ‘Neither agree nor disagree’, suggesting much of the public do not have strong views or knowledge on citizenship ceremonies.

Along political lines, variation in agreement and disagreement is present along party support. As Chart 12 above shows, across the statements, Conservative and Liberal Democrat votes are consistently a little more likely to agree with positive statements about citizenship ceremonies and slightly less likely to disagree with negative statements. The reverse is true of Labour voters. For example, a majority of Conservatives (53%) and almost half of Liberal Democrat voters (46%) say ‘Citizenship ceremonies help new citizens to build a sense of loyalty to Britain’, but only 39% of Labour voters agree, though this is still a plurality.

Intriguingly, Conservative Remainers emerge as the political grouping with the warmest feelings towards citizenship ceremonies. Sixty-three percent of Conservative Remainers say that ‘Citizenship ceremonies are an important way to welcome new citizens’, while only 45% of Conservative Leavers agree. This pattern of strong support for citizenship ceremonies among Conservative Remainers is repeated across all of the positive statements.

Currently, citizenship ceremonies are reserved purely for new British citizens. We tested whether our respondents think it would be worthwhile extending them to all members of the public turning 18, including current citizens. The results are shown in Chart 13 below.

Base: 2,001 UK adults

As seen in Chart 13 above, a majority of respondents answered ‘No’ (52%). In terms of socio-demographic differences, there is negligible variation in respondents’ opposition to this policy proposal, including across ethnicity and education status.

However, in terms of age, those aged over 55 are more likely to oppose (60%) the policy, than those aged 35 to 54 (49%) or 18 to 34 (43%).

Along party lines, as shown above in Chart 13, Conservatives are the most likely group (35%) to say that Brits should participate in a citizenship ceremony upon the age of 18, though a plurality (48%) still oppose the idea. A majority of Labour and Liberal Democrat voters oppose the policy (58% and 57% respectively).

Interestingly, a majority of Conservatives aged 18 to 34 (55%) and of those aged 35 to 54 (55%) do agree that compulsory citizenship ceremonies for Brits upon reaching the age of 18 should be introduced. In comparison, only 34% of the general public aged 18 to 34 and only 31% of those aged 35 to 54 agree.

There is no significant variation between all Remain and all Leave voters — a minority of 29% of both Remain and Leave voters support the policy.

Conclusion

This analysis revealed 9 main findings on UK public attitudes about the importance of, benefits of and criteria for citizenship.

- A clear majority of the British public think it is important for immigrants living permanently in the UK to become citizens. Overall, a strong majority of the public believe it is important for immigrants living permanently in the UK to become citizens. This consensus is shared between Remain and Leave voters and across almost all socio-demographic groups.

- The UK public are more likely than not to believe that the cost to an applicant of applying for citizenship as an adult non-EU applicant is too high. Though a plurality of the public feel that it costs too much to apply for citizenship as an adult non-EU applicant, there is a large divide between Remain and Leave voters, with Remain voters more likely to say the cost is too high. There is much variance by ethnicity and education status. Other White and BAME people are much more likely than White British people to say the cost is too high, as are graduates in comparison with non-graduates.

- The UK public thinks it should be cheaper for certain immigrant groups to become citizens, especially immigrants who work in key frontline sectors such as social care or the NHS, immigrants with skills which are in shortage and immigrants who have worked and paid taxes in Britain for more than five years. A majority of the public say every immigrant group we proposed deserves to receive discounted citizenship fees, especially immigrants who work in key frontline sectors such as social care or the NHS, immigrants with skills which are in shortage and immigrants who have worked and paid taxes in Britain for more than five years. Younger people are consistently more likely to support fee discounts for all immigrant groups. Though in general less likely than the general public to support citizenship fee discounts, Conservatives voters are still more likely than not to support a citizenship fee discount for every single immigrant group, with only some variation by age among Conservatives themselves, mirroring the age divide in the broader public.

- The UK public thinks it should be quicker for certain immigrant groups to become citizens, specifically those who work for the NHS, who are key workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and immigrants who work in social care. Despite resounding public support for discounting citizenship fees for certain immigrant groups, the public are less in favour of expedited routes to citizenship for certain groups. However, there are still groups who a majority of the public say deserve access to a faster route to citizenship: immigrants who work for the NHS, immigrants who are key workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and immigrants who work in social care. Conservatives are significantly less likely to support a faster route for all immigrant groups, though a majority support an expedited route for immigrants who work for the NHS and immigrants who are key workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The UK public firmly support easier access to citizenship for the children of immigrants who are born and raised in the UK. A majority of the public support discounted citizenship fees for these children, with a significant minority of the public believing these children should simply receive citizenship for free. Overall, a majority of Conservative voters are in favour of some kind of dispensation for these children. However, though only a minority of Conservative voters believe these children should pay citizenship fees in full, they are still much more likely to think so than other groups of voters.

- The UK public are more likely than not to believe that the Home Office should continue to apply the ‘good character’ requirement to child citizenship applicants. Ethnicity emerges as an important socio-demographic divider — while a majority of Other White people oppose the test’s application to children, a majority of all other ethnic groups support it. Otherwise, there is little variance by socio-demographic characteristics. Leave voters are more likely than Remain voters to support the good character test’s application to children. Conservatives voters are unanimous in saying that the Home Office should continue to apply the ‘good character’ requirement to child citizenship applicants.

- A clear majority of the UK public support the introduction of birthright citizenship. Support for this policy varies little across socio-demographic groups, though there is variance politically. Remain voters are much more likely to support birthright citizenship than Leave voters. The policy is also significantly more popular among Labour and Liberal Democrat voters, both of whom support it by a majority, in comparison to a plurality of Conservatives.

- A plurality of the UK public are generally supportive of citizenship ceremonies, but reject the idea that they should be extended beyond new citizens to all British citizens. The public appears to recognise the important role citizenship ceremonies can play in social integration, especially Conservative voters, although a significant minority of the public do not have strong views or knowledge on citizenship ceremonies. The majority of the public does not support the extension of citizenship ceremonies to all British citizens. There is negligible to little variance on this issue across socio-demographic and political groups, though Conservatives and younger people were more likely to support extending citizenship ceremonies to all young people.

Our polling shows that socio-demographic and voting characteristics are associated with differences in views on citizenship. Some characteristics emerge frequently as markers of differing public attitudes, while other socio-demographic characteristics are only linked to differences in views occasionally. Hence, we can divide these characteristics into two groups.

- A primary group with characteristics that are often associated with differences in views on citizenship: ethnicity, 2019 General Election vote and European Union Referendum vote.

- A secondary group with characteristics that are sometimes associated with differences in views on citizenship: age and education status.

Furthermore, with the exception of ethnicity, differences across these characteristics are consistent. In the primary group, being a Conservative or a Leave voter is usually associated with less positive views about citizenship, while being a Labour, Liberal Democrat or Remain voter is usually associated with more positive views.

In the secondary group, belonging to an older age group or being a non-graduate is sometimes associated with less positive views about citizenship, while being younger or being a graduate is sometimes associated with more positive views.

Many of these characteristics will be correlated, so we cannot attribute a causal relationship between being a member of a specific socio-demographic group or having a particular voting history and holding a certain attitude. For example, while both graduates and younger people are more likely to hold positive views on citizenship, rates of higher education are also higher among younger people.

New policies

Based on our findings, Bright Blue proposes three new policies that the Government should introduce.

Recommendation one: The Government should shorten the settlement requirements for all non-citizen COVID-19 key workers to two rather than five years, significantly reduce their residency fee by at least 75% and waive their citizenship application fee.

Pandemic key workers emerge in this report as a group the public feel is especially deserving of an easier path to citizenship, both in terms of process and cost. Coupled with the contribution of immigrant key workers to the national effort during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is right to reward them by easing their path to citizenship.

In September 2020, France ordered the prioritisation of citizenship requests from foreigners who “actively participated in the national effort” of the pandemic, including allowing eligible foreigners to become citizens after two rather than the standard five years of French residency.[xxiv]

Hence, we recommend that all non-citizen COVID-19 key workers who worked or will work as a key worker for at least six months during the pandemic should have their minimum continuous residence requirements of currently five years reduced so that they may apply for the appropriate form of settlement in their circumstances, such as Settled Status or Indefinite Leave to Remain, after only two years of living continuously in the UK. They will then be able to apply for citizenship having held this status for a year, as normal.

The costs for receiving citizenship are very high, with adult EU immigrants facing a £1,330 fee after being granted Settled Status and adult non-EU immigrants facing up to £3,719 in fees in total depending on their migration status. Therefore, we also propose that all non-citizen COVID-19 key workers who worked or will work as a key worker for six months during the pandemic be eligible to have their permanent residency fees discounted by at least 75%, in the case of non-EU immigrants, and their citizenship fees waived completely, in the case of all immigrants. Considering the revenue the Home Office generates from all residency and citizenship applications, even with these discounts, these fees will continue to generate a significant profit.

Following current government classification of key workers, this new rule would apply to those who have held a critical job in one of these sectors during COVID-19: health and social care; education and childcare; utilities and communication; food and necessary goods; transport; key public services; public safety and national security; and, national and local government.[xxv] This policy would offer approximately just over one million key workers who are not British citizens an accelerated and cheaper route to British citizenship.[xxvi]

Recommendation two: The Government should introduce discounted citizenship fees of at least 50% for low-income immigrants

We find that a majority of the public support citizenship fee discounts for various groups of immigrants, including immigrants on low-to-middle incomes earning below £30,000 a year.

Considering the contribution immigrants on modest incomes have made by the time they apply for citizenship, in general living at least six years in the UK and already paying a significant amount — in the case of non-EU migrants — for Indefinite Leave to Remain despite being on a low or middle income, the citizenship fee seems unfairly high and exclusionary.

We recommend implementing a permanent and substantial citizenship fee discount of at least 50% for immigrants earning below a certain income threshold who have been granted Indefinite Leave to Remain or Settled Status. This means citizenship fees would be means-tested to ensure those on low incomes are not excluded because of financial barriers.

Recommendation three: The Government should introduce free citizenship for children born and raised in the UK by parents who are not British citizens.

Currently the fee for a child’s application for British citizenship is £1,012. The High Court found last year that these high citizenship fees can lead the parents of such children not to apply for citizenship for them, leaving children who have lived their entire lives in Britain in limbo.[xxvii] The Home Office is currently being challenged in the courts to reduce or remove the citizenship application fee for children, but the outcome of this legal battle is unclear.[xxviii]

We recommend that the citizenship application process for non-citizen children born and raised in the UK be reformed, so that it is free for these children to apply for British citizenship. Considering there are multiple routes for such children to qualify for citizenship, this change should apply to all existing routes. This policy would give certainty and stability to young people for whom Britain is their only home by completely removing the financial pressure of their citizenship application fees from their families. It is also a policy which finds popular support, with the public strongly supporting cheaper access to citizenship for children who were born and raised in Britain but are not British citizens.

Acknowledgements

This report has been made possible by the generous support of Unbound Philanthropy. The ideas expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of our sponsors. I would like to thank Sunder Katwala of British Future and Will Somerville of Unbound Philanthropy for peer reviewing this report. I would also like to thank Ryan Shorthouse for his editing and feedback. I would especially like to thank Anvar Sarygulov for his guidance and advice. I would like to thank James Crouch and the Opinium team for their hard work and attention to detail.

The full data tables for the polling can be found here.

Footnotes

[i] Kristina Bakkær Simonsen, “Does citizenship always further Immigrants’ feeling of belonging to the host nation? A study of policies and public attitudes in 14 Western democracies”, Comparative Migration Studies (2017).

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Thomas Leibig and Friederike Von Haaren, “Citizenship and the Socio-economic Integration of Immigrants and their Children: An Overview across European Union and OECD Countries”, in Naturalisation: A passport for the better integration of immigrants and their children (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2011); Mariña Fernandez-Reino and Madeleine Sumption, “Briefing: Citizenship and naturalisation for migrants in the UK”, The Migration Observatory (2020), 2.

[iv] Home Office, “Control of Immigration: quarterly statistical summary, United Kingdom, quarter 4 2010”, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/116022/hosb0910.pdf (2011; Home Office, “How many people continue their stay in the UK or apply to stay permanently?”, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/immigration-statistics-year-ending-june-2020/how-many-people-continue-their-stay-in-the-uk-or-apply-to-stay-permanently#citizenship (2020).

[v] Dr Carlos Vargas-Silva and Dr Cinzia Rienzo, “Briefing: Migrants in the UK: An Overview”, The Migration Observatory (2019), 3; Home Office, “How many people continue their stay in the UK?”, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/immigration-statistics-year-ending-march-2020/how-many-people-continue-their-stay-in-the-uk#citizenship (2020).

[vi] Sam Joiner, Anna Lombardi, Sean O’Neill, “Hostile environment: Home Office makes £500m from immigration”, The Times, 11 August, 2019; Alan Travis, “Immigration fees rising sharply to pay for UK Border Agency cuts”, The Guardian, 28 February, 2011.

[vii] “Paytriotism, Becoming British is a costly business”, The Economist, 18 April, 2015.

[viii] Home Office, “Apply for citizenship if you have ‘permanent residence’ status”, https://www.gov.uk/apply-citizenship-eea.

[ix] Sam Joiner, Anna Lombardi, Sean O’Neill, “Hostile environment: Home Office makes £500m from immigration”, The Times, 11 August, 2019; David Bolt, “An inspection of the policies and practices of the Home Office’s Borders, Immigration and Citizenship Systems relating to charging and fees”, Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/792682/An_inspection_of_the_policies_and_practices_of_the_Home_Office_s_Borders__Immigration_and_Citizenship_Systems_relating_to_charging_and_fees.pdf (2019).

[x] Ethnicity of respondents is allocated into three groups: White British, Other White and BAME. White British refers to respondents who identify in certain ethnic categories: White English, White Welsh, White Scottish and White Irish. Other White refers to White respondents who do not identify as any of the White British categories. BAME people refers to respondents from Black, Asian and other minority ethnic backgrounds.

[xi] Mariña Fernandez-Reino and Madeleine Sumption, ”Citizenship and naturalisation for migrants in the UK”, The Migration Observatory (2020), 13.

[xii] Mariña Fernández-Reino and Madeleine Sumption, “Citizenship and naturalisation for migrants in the UK”, The Migration Observatory (2020).

[xiii] Sam Joiner, Anna Lombardi, Sean O’Neill, “Hostile environment: Home Office makes £500m from immigration”, The Times, 11 August, 2019.

[xiv] Kim Willsher, ”Foreign Covid workers in France to be fast-tracked for nationality”, The Guardian, 15 September, 2020.

[xv] Mariña Fernández-Reino, “Briefing: Children of migrants in the UK”, The Migration Observatory (2020).

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Project for the Registration of Children as British Citizens, ”News and updates”, https://prcbc.org/news-updates/ (2020).

[xviii] Home Office, ”Good character: nationality policy guidance”, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/good-character-nationality-policy-guidance (2017).

[xix] Join Human Rights Committee, “Good Character Requirements: Draft British Nationality Act 1981 (Remedial) Order 2019 — Second Report”, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt201719/jtselect/jtrights/1943/194302.htm (2019).

[xx] Home Office, ”Good character: nationality policy guidance”, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/good-character-nationality-policy-guidance (2017).

[xxi] Owen Bowcott, ”Home office ’applies good character test to children as young as 10’”, The Guardian, 9 July, 2019.

[xxii] PwC, ”Turkish citizenship by investment”, https://www.pwc.com.tr/turkish-citizenship-by-investment.

[xxiii] Patrick J. Lyons, ”Trump wants to abolish birthright citizenship. Can he do that?”, New York Times, 22 August, 2019.

[xxiv] Kim Willsher, ”Foreign Covid workers in France to be fast-tracked for nationality”, The Guardian, 15 September, 2020.

[xxv] ONS, ”Coronavirus and key workers in the UK”, https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/coronavirusandkeyworkersintheuk/2020-05-15#how-many-key-workers-are-in-your-area (2020).

[xxvi] ONS, ”Coronavirus and non-key workers”, https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/articles/coronavirusandnonukkeyworkers/2020-10-08#overview-of-key-workers-and-the-non-uk-population (2020).

[xxvii] Diane Taylor, ”High court says the UK’s £1,012 child citizenship fee is unlawful”, The Guardian, 19 December, 2019.

[xxviii] Project for the Registration of Children as British Citizens, ”News and updates”, https://prcbc.org/news-updates/ (2020).